BLACK WHITE and RED

The Facts, History and Science behind

The Chronocar

© 2017 Steve Bellinger

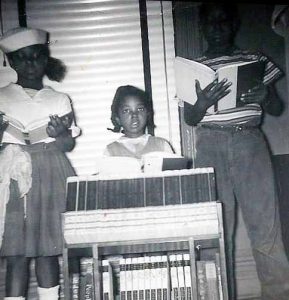

We were raised by a single mother who worked nights for a printing company, a one hour bus ride one way from our cold water flat on the West Side of Chicago. Her job was to help the press operators collate and pack books and magazines. She would often bring home stacks of scrap paper that we could draw and write on. More importantly she would bring home lots of paperback books and magazines, also. An avid reader herself, she could always be seen with her head buried in an Ellery Queen or Alfred Hitchcock novel, so we learned to love reading through her example.

She also made a point to bring home different kinds of books, from detective thrillers and romances to fantasies and westerns. One day she brought home a novel by Isaac Asimov and at 12 years of age I was instantly hooked on science fiction. It was still the golden age of sci-fi so I got to read some of the now famous works of Heinlein, Clarke, Bradbury and other masters of classic science fiction.

She also made a point to bring home different kinds of books, from detective thrillers and romances to fantasies and westerns. One day she brought home a novel by Isaac Asimov and at 12 years of age I was instantly hooked on science fiction. It was still the golden age of sci-fi so I got to read some of the now famous works of Heinlein, Clarke, Bradbury and other masters of classic science fiction.

We lived in simpler times. No computers, video games or anything like that and there wasn’t enough on television to fill our day. So we spent time actually playing and being creative; making up games, drawing pictures and even writing our own stories. By the time I was in high school I had decided that I would one day write a science fiction novel. After a few failed attempts at short stories resulting in some rather insulting rejection notices, I put that dream on hold.

I never gave up, though. I continued to write. Radio scripts, magazine articles, training manuals, even Junior High Sunday School lessons. With some encouragement from my wife Donna, I decided to take a stab at a novel again a few years ago.

My challenge was to write, not only a good science fiction story, but one that would embrace the Black Experience. It would be about time travel, so I needed an historical event to anchor the story. I was hoping to create as much of a “wow” factor in the history covered as with the science fiction. I found such an event that few people knew of, a little known but very significant race riot that took place early in the 20th Century in Chicago’s Black Belt, an area now known as Bronzeville.

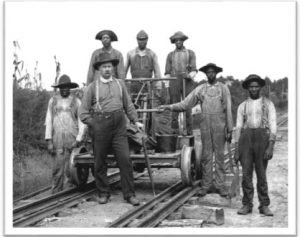

Now, I needed some interesting characters. I came up with Simmie Johnson, a young man born the son of a slave, working on a railroad construction gang 20 some years after the Civil War. What’s special about him? He was part of the .01% of the population born with a superior mind, a genius, a real challenge for a black man in the 1880’s. He manages to get an education and in his studies and research, discovers the secret of time travel and even designs a time machine, which he called a Chronocar. But this vehicle required technology that did not exist in his time.

Later in the story, about a hundred and thirty years later in fact, a young African American Illinois Institute of Technology student stumbles upon Dr. Johnson’s plans and builds a working Chronocar that he uses to go back in time to visit Johnson in the year 1919, just when the riot is about to begin.

The result is a story that has been praised and enjoyed by many. Even though much of it is loosely rooted in fact (the result of many hours of research), it is a fictional version of the events that took place during the Red Summer of 1919. Still, The Chronocar has actually helped to open the eyes of many to what life was like for blacks back then, and to the fact that Chicago suffered the bloodiest race riot in the city’s history in that year.

Black America in the 1800’s

“History is written by the winners.” —Napoleon Bonaparte

When I was a kid in school back in the middle years of the 20th Century, a lot of what we learned about slavery and the Civil War was quite whitewashed (pun intended). We got the idea that slavery was a bad thing, but no one would dare teach us the true horrors. Our history books did not even scratch the surface when it came to the brutality and inhumanity. It wasn’t until Alex Haley’s Roots TV program in the 1980’s that we got the first glimpse of what a nightmare slavery really was.

Back in the day, we were taught that Abraham Lincoln, the author of the Emancipation Proclamation that freed the slaves, was the Negro’s great hero, that we owed our lives and liberty to him. I also recall as a young student, believing that once the slaves were freed, life was suddenly better for them, that they had instantly become equal Americans, even as my life in the West Side ghetto of Chicago was far from idyllic.

that we owed our lives and liberty to him. I also recall as a young student, believing that once the slaves were freed, life was suddenly better for them, that they had instantly become equal Americans, even as my life in the West Side ghetto of Chicago was far from idyllic.

What we were taught about Lincoln was not quite true. In one of his debates with Stephen A. Douglass, Lincoln is quoted as saying, “I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races.”1 He believed slavery to be morally wrong, but he was not for equality; he actually wanted to send all the blacks back to Africa. Besides, the true purpose of the emancipation was to undermine the Confederacy. There were actually states, some above the Mason-Dixon Line, like Delaware, that were exempt.

Even though the idea of Black History Week dates back to 1926, I was an adult by the time Black History Month became a national observance.2 As more and more facts and details of history were revealed through books and television documentaries, I was soon dismayed to learn that many of our founding fathers like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and yes, even George Washington were at some point themselves slave owners.3

So the “facts” of history depend on who is telling the story.

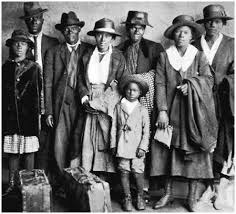

After Emancipation, ex-slaves were suddenly free, supposedly. But how free can you be with no education, no resources, and nowhere to go? Many stayed on and worked for the same masters, getting a pittance in compensation while others even remained voluntarily enslaved because they simply did not know any other way. Some tried to take control of their lives, leaving the plantation and finding other ways to survive.

This was how the character Simmie Johnson, ended up working on a railroad construction gang in the years following the Civil War. Usually blacks and Chinese workers did the heaviest, dirtiest of work, while the whites laid rails. Simmie swung a big hammer and drove the spikes that held the track in place, because he was big, strong and so good at it.

But Simmie was not your ordinary laborer. He was one of the extremely rare individuals on the planet born with the mind of a genius. I won’t give away any key elements of the story here, but suffice it to say that Simmie suffered the fate of many black men in the South at that time (and as recently as the 1960’s); he was forced to run for his life after inadvertently offending a white person.

Again, no spoilers here. I’ll just say that this genius of a man manages to get an education and reasons out the secret of time travel and designs a Chronocar that he cannot build himself.

THE RED SUMMER

The other protagonist of The Chronocar, Tony Carpenter, is a black Illinois Tech student in the year 2015. He discovers Dr. Johnson’s plans and builds a working Chronocar. His research helps him locate Dr. Johnson in the year 1919 and he takes the time machine back to that year to see the doctor to show him his great invention. There he also meets and becomes enamored with Dr. Johnson’s lovely daughter, Ollie.

1915 is thought to be the year when the Great Migration began. Thousands of blacks moved north, looking for freedom and opportunity. In a few  short years, the black population of Chicago more than doubled from about 44,000 to over 100,000. The Great War (World War I) was still raging, and thousands of men were still away fighting. Factories, warehouses and mills needed workers to keep running and many of the blacks were able to fill the gap left by the white men who had gone to fight.

short years, the black population of Chicago more than doubled from about 44,000 to over 100,000. The Great War (World War I) was still raging, and thousands of men were still away fighting. Factories, warehouses and mills needed workers to keep running and many of the blacks were able to fill the gap left by the white men who had gone to fight.

Then the war ended and the soldiers came home. White men, many Irish immigrants, returned to find that blacks had taken many of the jobs and were spreading out on the South Side. Economic pressure revived years of racial hatred and things just got worse as time went on.

It was the summer of 1919, the so called Red Summer, when things came to a head. A teenage boy named Eugene Williams decided to go swimming at the beach on 29th Street with some friends on a hot day in July. They found a home made raft under the pier and used it to paddle their way into th e cool waters of Lake Michigan. They were pretty much minding their own business until they inadvertently strayed over the invisible but clearly understood line into the “whites only” waters to the South. Some young white men began throwing rocks at them, and Eugene was hit in the head with a piece of brick. He slid into the water and drowned. His friends panicked and made their way back to the beach and told the black lifeguard what had happened. The police showed up as tensions between the crowds of whites and the blacks grew. Eugene’s friends pointed out the white man who threw the fatal missile, but the white policemen refused to do anything about it. A little later, when an altercation broke out between a white man and a black man, the police arrested and beat the black man.

e cool waters of Lake Michigan. They were pretty much minding their own business until they inadvertently strayed over the invisible but clearly understood line into the “whites only” waters to the South. Some young white men began throwing rocks at them, and Eugene was hit in the head with a piece of brick. He slid into the water and drowned. His friends panicked and made their way back to the beach and told the black lifeguard what had happened. The police showed up as tensions between the crowds of whites and the blacks grew. Eugene’s friends pointed out the white man who threw the fatal missile, but the white policemen refused to do anything about it. A little later, when an altercation broke out between a white man and a black man, the police arrested and beat the black man.

The resulting riot lasted 7 days. State Militia was called in to help quell the violence. 15 whites and 23 blacks were killed and more than 500 people (mostly black) were injured. 1,000 black families were burned out of their homes.4

Irish “clubs” were known to be major players in the violence against blacks: “One of the riot’s great mysteries is whether the city’s future boss of bosses, Richard J. Daley, participated in the violence. At the time, Daley belonged to the Hamburgs, a Bridgeport neighborhood club whose members figured prominently in the fighting. In later years, Daley repeatedly was asked what he did during the riots. He always refused to answer.”5

Chicago was not the only city to suffer riots during the Red Summer of 1919. Race riots broke out in Washington, D.C.; Knoxville, Tennessee; Longview, Texas; Phillips County, Arkansas; and Omaha, Nebraska6

| “Every thoughtful Chicagoan should know about the city’s 1919 race riot. Its tragic loss of lives and property was not the end of the story, however. For in and through it, African Americans fought back and proved that the Black Belt (now referred to as Bronzeville) was here to stay. They demonstrated the truth that America is not a single racial group but a value system that all races and creeds can make their own; that—as the Founding Fathers recognized—freedom is the glue, but one which must be perpetually renewed through ceaseless struggles for justice and inclusion. Mr. Bellinger’s book advances this awareness through a wonderful narrative, set in the part of town (the near South Side) where Chicago’s history is truly rooted.”

–Dr. Ralph A. Pugh, University Archivist at the Illinois Institute of Technology. |

HAVE THINGS CHANGED IN 100 YEARS?

“Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” —George Santayana7

Some will say things are just as bad as ever, that nothing has really changed, but I don’t believe that to be true. In recent years I have lived in neighborhoods where I would not have been welcomed 40 or 50 years ago. Chicago has seen 2 black mayors and our nation elected a black president—twice. It’s safe to say that there would have been zero chance of either 50 or more years ago. Representation of blacks (and other ethnic groups) in business, entertainment, law enforcement, etc., is significantly better, although there is always room for improvement.

Still, over the decades, the bloody race riots have continued. From 1921 in Tulsa, Oklahoma and 1943 in Detroit to the historic Watts riots in Los Angeles in 1965. I was personally a witness to race riots in Chicago during the 1960’s. I vividly recall, as a teen, watching out of my bedroom window whilst an angry crowd came down Roosevelt Road on the West Side. “Word on the street” had been that there would be trouble and folks were told to stay inside. I watched in dread and despair as the mob broke windows and looted stores, including the little candy shop across the street that was run by the Swedish lady who was known to give free candy to kids when they had no money. Two years later, we lived only three blocks from the inferno that was Madison Street the day Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968. I can still see the orange glow in the sky as we watched from our back porch, ready to grab our valuables and get out if the flames were to spread south. Fortunately it never came our way.

By the time I got to college, it seemed as if the days of the race riots were over. But the only thing that really changed was the proliferation of video cameras and eventually smart phones. Outrages like the beating of Rodney King in 1992 were captured on video for the world to see. In response, the violence returned.

So even though I personally feel safer in almost any neighborhood in Chicago than before, and opportunities are much better, the violence remains. Because many of the inequities remain. In the 21st Century, when I had hoped racial prejudice and strife would be little more than history, these evils are rearing their ugly heads again. The racism that I thought and hoped was dead is now manifesting itself subtly and openly in our institutions and flourishing hate groups. Not only is it dangerous to be Black in America; now you have to be wary if you’re Muslim, Latino, gay, female, or even a little child.

Or, to put it in the words of French critic and novelist Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr; “the more things change, the more they stay the same”8.

HISTORICAL PLACES AND THINGS

In The Chronocar, Tony Carpenter takes his time machine back nearly 100 years. He is surprised at what he sees. Like many present day Chicagoans, he had no idea how long some things have been around.

The “EL”

Tony is shocked to see the 47th Street elevated station in 1919. But the elevated trains have been around for a very long time. The first elevated line opened in 1892 and went from Congress Street downtown south to 39th street. This was, of course, before electric trains; the first “el” was pulled by a small steam engine. This was followed by elevated lines to the West and Northwest sides of the city, and later a line was built that encircled the downtown area called The Union Loop or as we know it now, just The Loop (yes, the area is named after the elevated line).9 Originally these lines were owned by different private transit companies, and the buses and street cars were separately operated. It wasn’t until 1945 that an Act of the General Assembly of the State of Illinois created the Chicago Transit Authority, finally unifying the city’s transit system.10

Incidentally, the portion of the CTA Green Line that runs over Lake Street is the oldest existing elevated line, put into service in 1893.11 How has it survived that long? Turns out it was built using what was then a new riveted plate steel construction method that was perfected a few years earlier in the building of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, France.12

Downtown Chicago

Dr. Simmie Johnson takes Tony Carpenter for a ride in the summer of 1919, and Tony is surprised again at what he sees. As they drive North on Michigan Avenue, they pass the Art Institute, complete with the lions. The beach comes all the way up to the street and the trees that are there are little more than saplings. State and Madison is a nightmarish traffic jam of cars, streetcars, trucks, and horse drawn carriages. He also sees the Marshall Field’s store and the amazing Chicago Theatre sign, looking pretty much the same as now.

Dr. Simmie Johnson takes Tony Carpenter for a ride in the summer of 1919, and Tony is surprised again at what he sees. As they drive North on Michigan Avenue, they pass the Art Institute, complete with the lions. The beach comes all the way up to the street and the trees that are there are little more than saplings. State and Madison is a nightmarish traffic jam of cars, streetcars, trucks, and horse drawn carriages. He also sees the Marshall Field’s store and the amazing Chicago Theatre sign, looking pretty much the same as now.

Illinois Institute of Technology

Tony is an IIT student in 2015. As their tour of the city ends, Tony coaxes Dr. Johnson to turn onto 35th Street and they see, not IIT but the Armour Institute, which opened in 1893. IIT was a merger of the Armour and Lewis Institutes in 1927. They park on 31st street across from today’s Main Building and alongside Machinery Hall where Tony’s adventures continue.13

Tony is an IIT student in 2015. As their tour of the city ends, Tony coaxes Dr. Johnson to turn onto 35th Street and they see, not IIT but the Armour Institute, which opened in 1893. IIT was a merger of the Armour and Lewis Institutes in 1927. They park on 31st street across from today’s Main Building and alongside Machinery Hall where Tony’s adventures continue.13

There were several early African-American graduates of Lewis, Armour, and Chicago-Kent College of Law. As there were numerous African-Americans enrolled in Lewis and Armour when they merged, IIT has always had blacks in its student body.14

White City

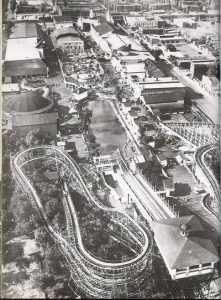

I was surprised when I discovered in my research that there had been a major amusement park on the South Side at that time. White City, which stood at the corner of 63rd and Cottage Grove, featured many rides and attractions left over from the Columbian Exposition of 1893. It had a huge Ferris wheel, at least one roller coaster and a wooden escalator that took you to the top of the Shoot the Chutes ride. An alabaster tower stood at one end topped with a sweeping searchlight. It must have been an amazing site and a fun time.

I was surprised when I discovered in my research that there had been a major amusement park on the South Side at that time. White City, which stood at the corner of 63rd and Cottage Grove, featured many rides and attractions left over from the Columbian Exposition of 1893. It had a huge Ferris wheel, at least one roller coaster and a wooden escalator that took you to the top of the Shoot the Chutes ride. An alabaster tower stood at one end topped with a sweeping searchlight. It must have been an amazing site and a fun time.

Time Travel, Science Fiction

and Historical Fiction

A surprising number of people who say they hate science fiction have enjoyed reading The Chronocar. Some have said that it seems more historical fiction than science fiction.15 The big surprise to me is how differently people see the same story. It really makes no difference what you think it is as long as you enjoy it.

Still, I think the reason people who dislike sci-fi enjoy The Chronocar is because science fiction has been so diluted and confused in recent years that few people know what real science fiction is. Popular culture lumps everything from Tolkien fantasy, Marvel superheroes to horror into the same pot as sci-fi. Not so. In a true science fiction story, the science, whether real or imaginary, must be central to the story; so much so that if you removed it, the story would fall apart. There is little or no science in fantasies and most superhero and horror stories. In fact, by that definition, Star Wars is not science fiction.16

Historical fiction, I feel, is based on people who can exist in the same time in history. For example, a story about Harriet Tubman meeting Abraham Lincoln would be historical fiction. They were contemporaries and Tubman actually had the opportunity to meet Lincoln but refused.17 In The Chronocar, Tony Carpenter is a man from the year 2015 meeting with Dr. Johnson almost a century in the past. This could only be possible through time travel. They have to deal with each other’s differences and Tony’s modern technology (his smartphone) gets him in trouble. That is science fiction.

At a critique reading of a chapter of The Chronocar before it was published, one of my fellow writers ripped into the time travel theories that are the basis of the book. Being a very learned man himself, he challenged the science of time travel as discovered by Dr. Johnson and was concerned that people reading it would believe it to be true. I thanked him. I have since had others pull me aside and ask if the theories in the book were true. Of course they are not. It is, after all, science fiction. The theory and mechanism of time travel in The Chronocar were designed to serve the story, not to offer any competition to current scientific theory.

Is time travel possible? Dr. Stephen Hawking theorizes a way to travel to the future by finding and interacting with the event horizon of a black hole. When you get back home, it would be years in the future. But you could never go back to the past. This actually makes sense, but the nearest black hole is some 27,000 light years away, so it is still rather problematic. There really is no way you can climb into a time machine, whether it be a metal sphere, hot tub or telephone booth and travel back in forth in time at will. At least, I don’t believe it is possible.

Except in science fiction.

–Steve Bellinger

Footnotes

1 http://www.history.com/news/5-things-you-may-not-know-about-lincoln-slavery-and-emancipation

2 https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_History_Month

3 http://www.revolutionary-war.net/slavery-and-the-founding-fathers.html

4 http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/chicago-race-riot-of-1919

5 http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/chi-chicagodays-raceriots-story-story.html

6 http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/chicago-race-riot-of-1919

7 https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/George_Santayana

8 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Baptiste_Alphonse_Karr

9 http://www.chicago-l.org/history/4line.html

10 http://www.chicago-l.org/history/CTA1.html

11http://forgottenchicago.com/features/remnants-of-the-l/

12 Borzo, Greg. The Chicago “L”. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2007 P11.

13 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illinois_Institute_of_Technology

14 http://archives.iit.edu/people/IITArchives_People_African-Americans.pdf

15 http://www.blacksci-fi.com/review-chronocar/

16 http://www.esquire.com/entertainment/movies/a32507/george-lucas-sundance-quotes/

17 http://civilwarsaga.com/harriet-tubman-didnt-like-abraham-lincoln/